What I learned in conversation with Dr. Lawrence Brown

A record number of protests following the tragic deaths of Black people due to racism and bias during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic shook the nation and the world in 2020. It highlighted for some and reminded others of the inequalities and injustices that plague our society and disproportionately impact Black people. While Black people from all walks of life are impacted by racism and oppression, historically segregated, redlined Black neighborhoods in cities across America bear the brunt of surveillance, disinvestment, and displacement that results in a consistent loss of Black life. We’ve heard the names, or know the people, and we see ourselves in the names, hashtags, and stories from today and yesterday.

This history is one that many of us know personally. It started when the first Africans were displaced from their countries, enslaved, and brought to the shores of our present-day United States to labor and build this country for what it is today: “the land of opportunity.” These early Africans were not seen as human beings, but as property with the purpose of laboring and producing goods and services for which they would receive no benefit. As property, the conditions in which they lived were an afterthought, and enslaved Africans received the scraps of everything unwanted by the slave masters.

When we look at redlined Black neighborhoods today, we see a similar reality: Black residents are allocated the scraps of goods and services and told to make do. They are told to work, to learn, and to pull themselves up by their bootstraps and do better in the face of exploitation, deprivation, and violence. In 2020, we faced a double pandemic of racism and COVID-19 and it was hard to ignore. It had the country talking and acting on a broader scale than I had ever seen in my millennial lifetime which provided a glimmer of hope and optimism. But then, things started to feel performative – the buzzwords, “blackouts,” and statements. What felt lacking was a true understanding, thoughtfulness, and substance to create long-term systemic change.

When I began reading Dr. Lawrence Brown’s book “The Black Butterfly: The Harmful Politics of Race and Space in America,” I felt the understanding, thoughtfulness and substance to create the long-term systemic change that we need in our communities to truly make Black Lives Matter. I was drawn in by the books’ description of early Baltimore history that explained the migration, displacement, and segregation of African Americans in redlined neighborhoods and how it’s been maintained today. It felt like reading about my own family’s origins in the city via the Great Migration from North Carolina and into a redlined West Baltimore neighborhood within what Dr. Brown calls Baltimore’s “Black Butterfly.” I learned of Baltimore’s history of redlining, all its players, and the blueprint it provided for hypersegregated cities across the country.

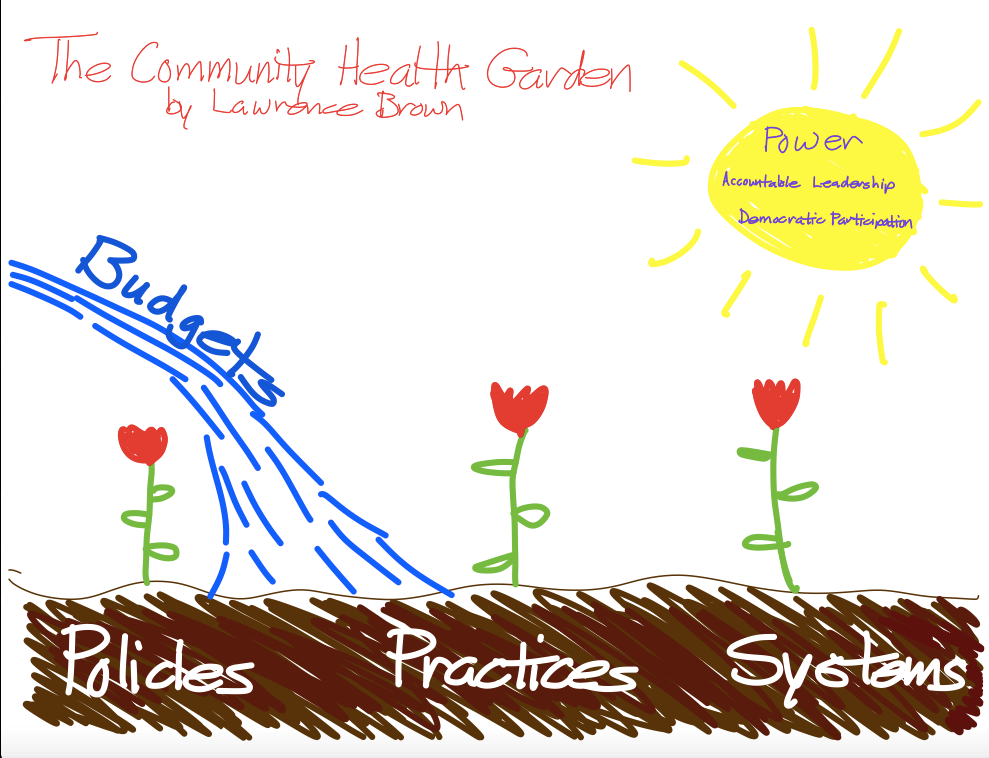

After this heavy history and its ramifications today, Dr. Brown provides hope with practical solutions for healing and restoring redlined communities as outlined in his Community Health Garden. The garden focuses on improvements to policies, practices, systems, and budgets, and inspires a healthier and promising outlook for historically redlined Black neighborhoods and its residents.

On February 10, BRHP had the opportunity to sit down in conversation with Dr. Brown to discuss his book and approach to healing the Black Butterfly. I left feeling empowered knowing that systemic change is possible and can start at the very local level with people like you and I who understand our “normal” isn’t working for any of us and we need change.

Watch the replay of our event below and let us know what you think.